Opinion

Transformation among the Western Himalayan Gaddi Tribe of Himachal Pradesh: Question of Identity and Modernity

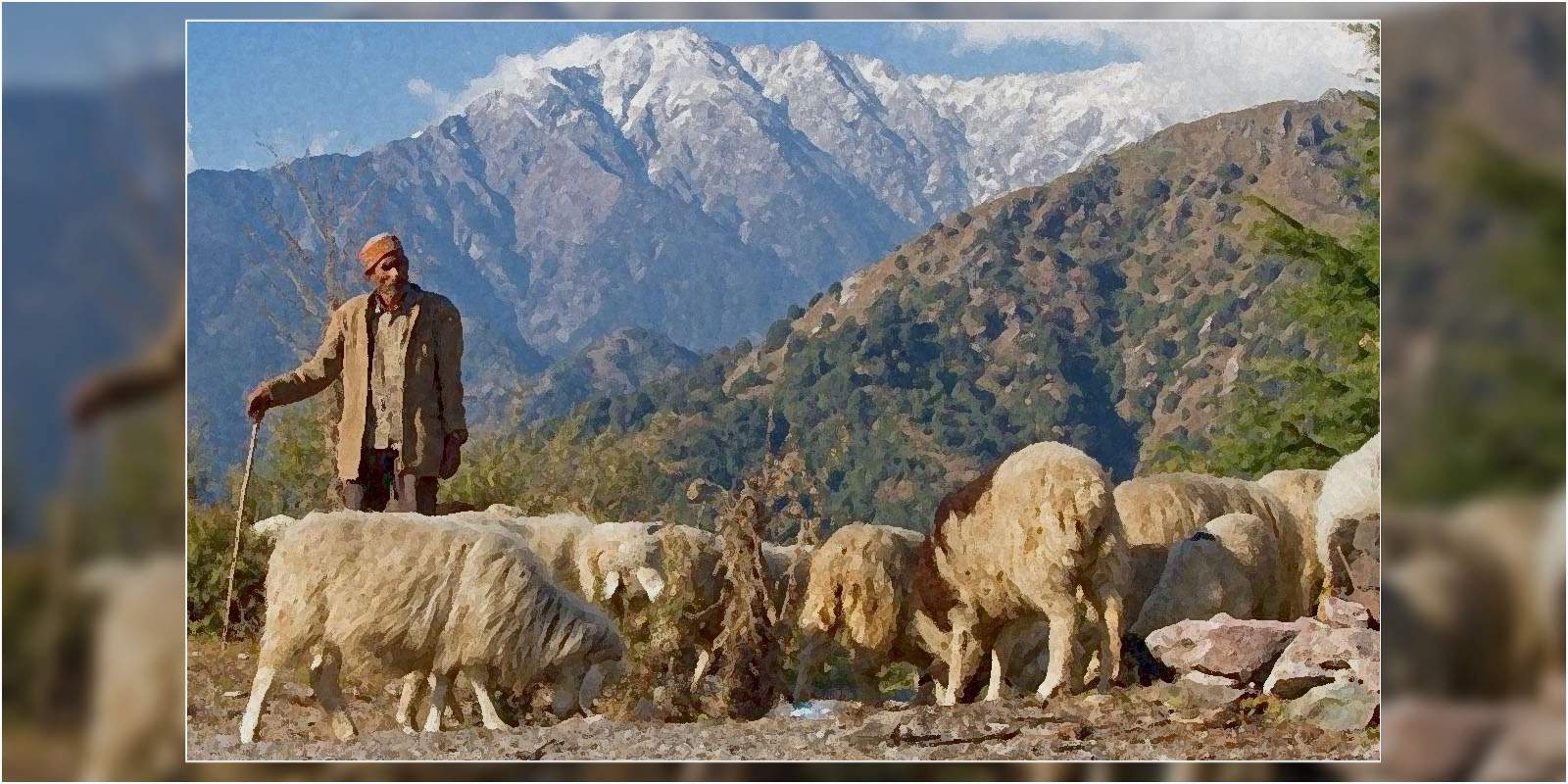

The piece deals with the Western Himalayan Gaddi tribe which mostly resides in Himachal Pradesh. They live in Chamba and Kangra districts of the state and Bharmour -a sub- tehsil of Chamba district- used to be the abode of majority of the Gaddi population. The work traces the transformation among this tribe and focuses majorly on the question of identity and modernity.

Origin of the Tribe

Verbal as well as the written records reveal that Bharmour the homeland of the Gaddis, was the first place to be founded in present day Chamba district. Bharmour is said to have been founded by a man named Maru in 500 AD. It is believed that he entered the area from Kalpa (a place in Kinnaur District). But it was during the time of a king named Meru Varman the fifth in the seventh century AD (660 AD) that the area came into limelight. Though the origin of Gaddis in Bharmour is still a mystery but some consider the Gaddis as descendants of the Aryans who either settled directly in Bharmour from Central Asia or migrated from the adjoining plains to this area. On the other hand, Ilbetson states that the Gaddis inhabited the snowy hill ranges that divide Chamba and Kangra from Lahore in the 16th century. On their arrival in these areas, they faced problems of food and shelter acutely and thus they chose to acquire a pastoral occupation. So, they owned sheep’s and goats which provided them food and clothing and forced them to adopt a nomadic way of life in search of pastures for their herds. The goat milk provided them food, while the wool of sheep enabled them to make warm clothes, they needed. It is due to this occupation that they are called Gaddi, i.e., a word resembling closely with the word ‘Gadri’ or ‘Gadria’, meaning a ‘shepherd’. The whole area of Bharmour sub-tehsil, where the Gaddis started living, has since been known as ‘Gadhern’ or ‘Gaderan’, meaning a place where the Gaddis live.

Later, due to the hardships of climate, shrinking of grazing land and the hard way of family life, the Gaddi families started settling down in Kangra district all along the lower hilly ranges of Dhauladhar, making their permanent homes there and changing from a semi-nomadic mode of life to a sedentary one. The ancestral linkages of the Gaddis of Kangra district with those of Bharmour sub-tehsil of Chamba district also stand testimony to the fact that they have from time to time migrated from the higher altitudes of Chamba district to the lower reaches of Kangra district. Some of them still have their names in the land records of Chamba district, even though they have been living for long in Kangra and elsewhere. This was also the main argument which helped provide Tribal status to the Gaddi’s living in Kangra district in 2002.

Culture and Society

The Gaddis living in both the districts of Chamba and Kangra are a Hindus, their castes being Brahmins, Rajputs, Khatris, Thakurs and Rathis. The Brahmins among the Gaddis are called Bhat Gaddis, they act as priests for all religious and social ceremonies, including weddings of the other castes of the Gaddis. Further, people of the tribe speak Gaddiyali which can be broadly categorized under the Western Pahari group of languages. Then, marriage among the Gaddis is mostly monogamy and is arranged with the consent of the parents. Widow re-marriage, which also includes levirate and surrogate marriages, i.e. marrying the deceased husband’s brother and the deceased wife’s sister respectively, is also permissible in Gaddi society. It is arranged without formal, elaborate marriage celebrations, for it means just accepting him or her as husband or wife after giving a feast to the relatives and presenting a gold nose ring (balu) to the bride. Divorcees are also allowed to remarry according to any of the marriage system referred to earlier.

Traditionally, the Gaddis are by and large religious and superstitious people. Since they are the inhabitants of the mountains, they claim to have the direct blessings and protection of Lord Shiva and thus are staunch followers of Shaivism. Besides Shaivism they also are believers in the Shaktivism sect of Hinduism as well as other gods, goddesses, and spirits, which are worshipped at the family and/or community level. Snake worship is also very common among them. The Chaurasi Temple in Bharmour is for instance, an important community level worshipping place for the Gaddis. Mani Mahesh, a snowclad peak near Bharmour which is believed to be the abode of Lord Shiva, is another holy community pilgrimage place for the Gaddis. To ward off the evil effects of advertent or inadvertent omissions in the timely worship of the deities and spirits, the Gaddi families make offerings by means of feasts or sacrifices of sheep or goats. The traditional Gaddi festivals are also special occasions to pray to their gods and goddesses. These traditional festivals are: Sair Sankranti, Lohri, (Makar Sankranti), Joru Patroru Sankranti, Dholru Sankranti, Basoa Sankranti, Shivratri and Holi. Pilgrimages, locally called jatras/yatras, are also made. For example, a jatra/yatra called Nuala is made in the honor of Lord Shiva in which very famous is Chhatrari Jatra, Manimahesh Jatra. The Minjar Fair of Chamba and Bharmour Fair of Bharmour also bring the Gaddi congregation very near to their deities, providing them with special occasions for worship.

Traditional Power Institutions

Like other tribal communities, the Gaddis have had their own traditional political system, which constituted an important part of their social structure to regulate and direct the proper functioning of many of the activities of their social organization. This traditional political system used to function under a political body constituted by the then Raja of Chamba. The Gaddis had a political system subservient to the monarch or King (Raja). All the people known as subjects (Praja) would carry out the orders by the king who had the supreme authority. The King used to appoint royal representatives to ensure his proper rule over the society. This political body was constituted to maintain law and order and consisted of functionaries like Chad, Likhnara, Darbail/Darbyal/Ugrakar, Mukadams, Batwal and Jutiar and their political body was called by various names such as Bradari, Kamdar and Panchi. All the functionaries except the Batwal and Jutiar who belonged to a Scheduled Caste, are Gaddis. Higher caste people enjoyed the powerful positions given by the king. In the hierarchical order, the Chad was considered the highest, followed by Likhnara, Darbail/Darbyal/Ugrakar, Mukadams, Batwal and Jutiar. Chad and Likhnara wielded the powers of the magistrate, judge and tehsildar and were given the responsibility to decide all matters concerning land or family in the villages called Kothi or Ilaqa or Pargana (an area usually consisting of 26 villages). Darbail/ Darbyal/Ugrakar used to perform the functions of a Lambardar of today, collecting land revenue from the villagers in a Kothi or Ilaqa or Pargana.

Mukkadams used to be the members of the political body for consultation on various matters by Chad, Likhnara and Darbail /Darbyal/Ugrakar. Batwal and Jutiar used to function respectively as senior and subordinate messengers or communicators of all kinds of messages sent by Chad, Likhnara, Darbyal/Darbail and Ugrakar from time to time to the population living in the area under their jurisdiction. The functionaries mentioned above used to work under the overall supreme control of the Raja of Chamba. The State of Chamba at that time was divided into five Nazarats, of which Bharmour sub-tehsil was one. The Raja being political administrator of all Wazarats, used to appoint Wazirs and other senior functionaries of these Wazarats. This political system prevalent that time among the Gaddi community is now almost defunct.

The Post-Independence era commenced with a new political system taking into its fold the entire village population of the country, including tribal and non-tribal communities. The Panchayat system affected all the traditional political organizations of the tribal areas. The Gaddis also could not escape from the new political developments in rural India. Their traditional political body once named by them as Kamgar or Bradari or Panchi was replaced by the Statutory Gram Panchayat. Although, the traditional power structures are not in prevalence to that extent but still there are some social roles which must be abided by the members of the community to maintain the smooth functioning of the social relations. Most of the disputes are settled by the caste (Biradari) panchayat. This system is prevalent especially in Kangra district, where the Panchayats also have non-tribal Pradhans, Sarpanches and Panches. In Chamba district, the Gram Panchayats in Gaddi villages have mostly Gaddi Sarpanches, Panches and even Pradhans, so the cases are discussed straight away at the Panchayat level and not at the community level.

Transformation Process

In Gaddis transformation can be seen on their socio-economic institutions due to their cultural contacts with other communities. The Gaddis have over the time come into contact with the surrounding rural and urban communities, which have been changing over the decades. The major factor responsible for this contact is education. All their socio-economic institutions are now changing at a faster rate in the educated group than in the non-educated one. These institutions, inter alia is the family, its size and norms, marriage pattern, religious beliefs, kinship system, its terminology and usage, political system, occupational structure and economy, approach to class hierarchy, economic status and job preference. The participation of the educated Gaddi community in the modern political institutions may be seen from the fact that many educated Gaddis have started contesting elections to the Legislative Assembly of Himachal Pradesh. There are number of educated members of the Gaddi community who are Member of Legislative Assemblies. Recently, in 2019 Kishan Kapoor, a former minister in the state government also became the first member from the Gaddi community to be elected as a Member of the Indian Parliament.

Concerning the economic aspect, the traditional occupations of the Gaddis include agriculture, sheep-rearing and other subsidiary occupations like slate quarry work, priesthood, labour work, masonry work, shop keeping, rice milling, cattle rearing, spinning, weaving of wool etc. But in the past decades revolutionary changes can be seen in their traditional occupational structure with a considerable number departing from traditional occupations and acquiring service and wage-based occupations. The Gaddis have especially moved towards the tourism sector jobs as their native places are being exposed to tourists. Many have started working in the hospitality sector and have set up their own business including hotels and travel agencies.

Social and Cultural Transformation

For Gaddis non-observance of traditional religious practices is very difficult as they fear, that by doing that, they might bring a calamity for their family or the village. But education has affected such a belief. Since, many of the educated members of the Gaddi households have jobs, their role in traditional, social, and religious activities of the family or the village community decreases, whereas their role in the occupational and other social activities at the place of their employment becomes dominant. Such a change in roles from the traditional to the modern has made a change in their attitude towards their traditional beliefs and practices. Their attitude towards the Scheduled Castes is fast changing because of the spread of education among the latter, contributing to their economic uplift. Education is bringing about an attitudinal change in the Gaddi community in two ways; one, it is enabling the Gaddis to overcome the inferiority complex they used to suffer from other communities and second, it is enabling them to dispel from their minds apathy they used to have for people belonging to the Scheduled Castes. Thus, this two-way role of education is a big and positive step forward in understanding inter-population relations as well as intra-population relations in their social set-up.

Conclusion

Transformation can be observed in the Gaddi community from within, where education has been a catalyst of socio-economic change, it has also made this tribe a forward-looking tribe and the forces of change are making inroads very speedily. Consequently, the political participation, occupational changes are further propelling the change and making this tribe modern and malleable. On the flipside, modernization forces are creating internal contradictions, which are posing serious challenges before the community. Many still practice their unique traditions but to preserve their culture and identity these tribes should be allowed to have institutions according to their traditional customary laws and practices. But with increasing globalization this has become difficult, and they are on the verge of losing their identity. The pace of evolving changes with time has also affected the living style of this Gaddi Tribe, which poses a great threat to their culture.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Himachal Watcher or its members.

Opinion

A young leader’s activism combined with the concept of ‘Himachaliyat’ and ‘Virbhadra Singh Vikas Model’ may be a gamechanger for the Congress in Himachal

By – Vishal Sharma, who is a researcher and consultant with an LL.M. in Legal & Political Aspects of International Affairs from Cardiff University, United Kingdom.

Full disclosure: He is currently a Research Coordinator with the Himachal Pradesh Congress Committee and has worked as a consultant aligned with the All India Congress Committee in the recent Uttar Pradesh assembly elections handling field operations in mainly Bareilly, Rae Bareli, and Varanasi districts.

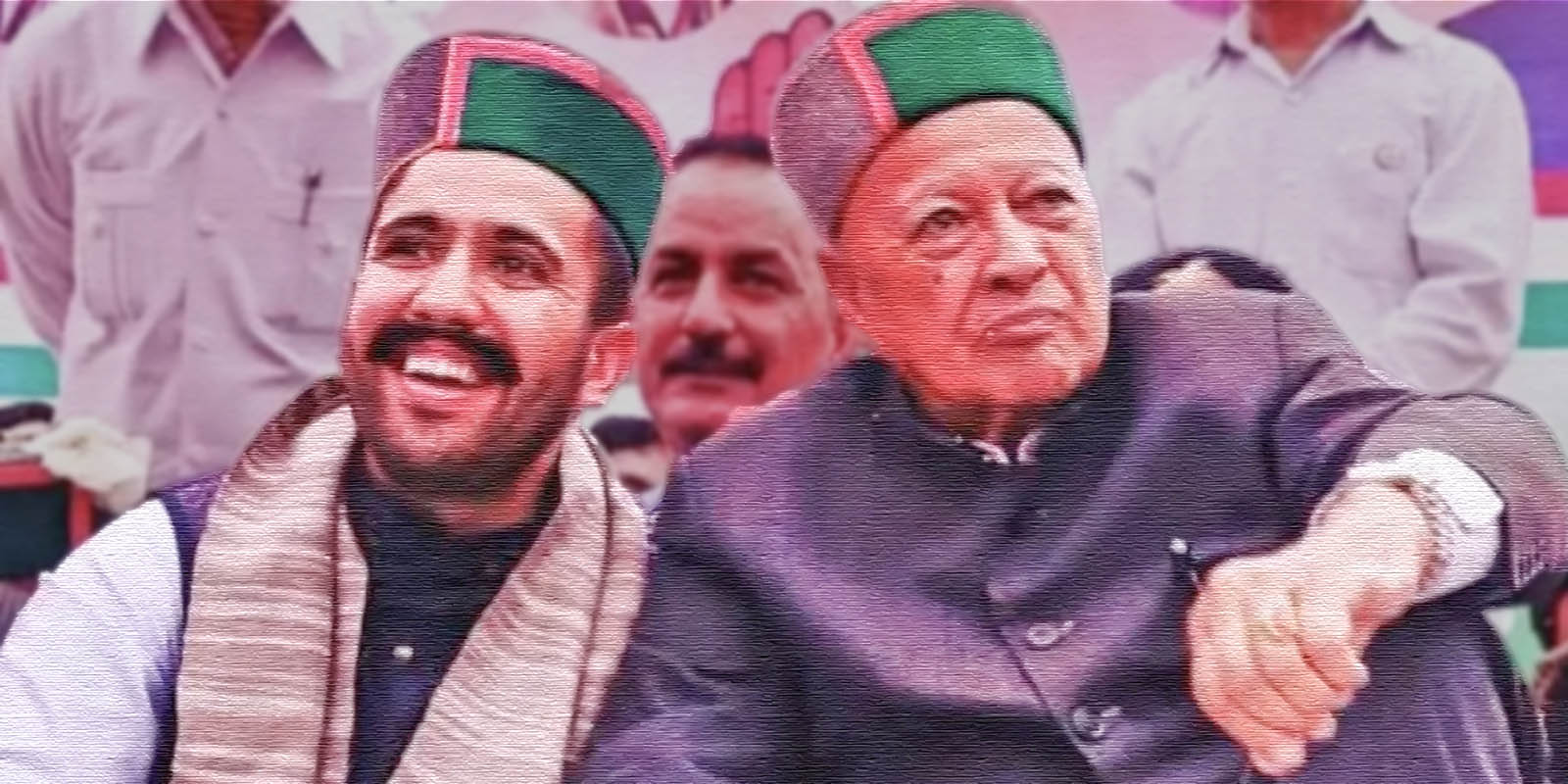

Building on the legacy of his father the late Virbhadra Singh, Vikramaditya Singh’s electoral campaign for the assembly elections may deliver an unexpected gift to the Congress in this western Himalayan state.

As political parties in India battle it out for the upcoming 2024 general elections, observers of Himachal Pradesh may spot some interesting -trends in this western Himalayan state. Leaders of national parties may even learn a thing or two if they can look beyond their centralized tunnel visions.

The ruling BJP has had remarkable victories in numerous state elections like Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Goa, and Manipur. Many political pundits have upheld these results as the final nail in the coffin of the Congress.

But in Himachal, it’s a different story.

Going by inputs from party workers and reporters on the ground, BJP’s momentum might break in Himachal. And, contrary to general perceptions and to the surprise of even many Indian National Congress leaders, the Congress is actually doing well here.

There are multiple factors behind this development, including the BJP government’s poor performance in the state, especially its poor handling of the Covid crisis.

The efforts of numerous state leaders have also contributed towards this upward trajectory. What stands out in this context is the electoral campaign being run by Vikramaditya Singh, a 32-year old member of the legislative assembly from the Shimla (Rural) constituency.

He is the only son of late Virbhadra Singh who passed away in 2021, one of Himachal’s most iconic political figures. A six-time chief minister of Himachal Pradesh, nine-time member of the state’s legislative assembly, and five-time member of the Indian Parliament, he remains unmatched in political stature, popularity, and acceptance.

It’s a tough act to follow. Which is perhaps why Vikramaditya, a career politician, and Virbhadra Singh’s only son, can’t afford to rest on his father’s laurels. He chose to jump into the fray on his own steam and cut his political teeth as a youth activist before being elected president of the Himachal Pradesh Youth Congress in 2013.

The elder Singh, whose political activity began tapering off in 2017, had consistently upheld certain values throughout his political career spanning six decades. His values and achievements, repackaged in catchy terminology, are not only keeping his legacy alive, but are fuelling his son’s campaign.

Former Deputy Advocate General of Himachal Pradesh Tarun Pathak believes that “Vikramaditya Singh is slowly and steadily emerging as the pan-Himachal leader which the Congress party desperately needs”.

“Vikramaditya’s style of taking on the BJP leadership in the state also reminds older activists of his father” says Devinder Bushahri, Spokesperson of the Himachal Pradesh Congress Committee.

Many believe that this together with his youth, social media prowess, and a solid campaign are making him a potential gamechanger in the upcoming electoral battle.

BJP’s momentum runs into the Himachaliyat Wall

The first weapon in Vikramaditya Singh’s arsenal is his narrative of ‘Himachaliyat’ – a term he coined based on his father’s pluralistic regional ideology.

‘Himachaliyat’ encapsulates the idea that the region and its people will decide their future without outside interference.

It also exemplifies a diverse, harmonious culture evident in local festivals, language dialects, cuisines, and clothing.

He is fiercely protective of this centuries-old indigenous tradition of inclusivity and syncretism in this hilly homeland of Himachal.

This also serves as a counter to the hegemonic narrative of caste and religion that is the hallmark of the ruling BJP. He often refers to how the BJP-led government and the Sangh Parivar, Saffron family, of hyper-nationalist organisations, have tried to erode Himachaliyat.

“Himachal’s election will be fought on regional issues, it will be fought on the issue of Himachaliyat. We will not tolerate elements who try to divide us on sub-regional, caste-based and religious lines for political gains,” says Vikramaditya.

He fiercely opposed the BJP-led state government’s attempt in 2018 to amend Section 118 of the Land and Tenancy Act, 1972 that restricts outsiders from buying agricultural land in Himachal Pradesh. He also fought the proposal to change the name of Shimla to Shyamala.

His efforts contributed to public awareness on these issues. Both proposals were shot down.

View this post on Instagram

Vikramaditya Singh’s Instagram reel on Himachaliyat has garnered over 101K views since 23rd July 2022

‘Virbhadra Singh Vikas Model’ over ‘Delhi Model’

The second prong in Singh’s campaign arsenal is what he calls the Virbhadra Singh Vikas Model, highlighting and promising to take forward the numerous developmental works of his late father.

“This terminology is gaining popularity and is proving to be a strong counter to the AAP and its Delhi model,” comments Devender Sharma, a political scientist and former research associate at the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies (IIAS), Shimla.

Many leaders from the Aam Aadmi Party’s state unit in Himachal have left the party including its former state president. The AAP had tried to replicate in Himachal how they governed Delhi, touting the AAP’s transformation of the capital’s education sector.

“Virbhadra Singh ensured that education reaches to every corner of the state, a difficult task given the state’s tough terrain and tricky geographical location, thus comparing the developmental works in hilly Himachal with the Delhi plains in uncalled for,” says Sushant Keprate, secretary, Himachal Pradesh Congress Committee

Scoffing at their efforts, Vikramaditya Singh highlights the numerous developmental works undertaken during Virbhadra Singh’s tenure.

Actual work on the ground over decades takes Vikramaditya’s narrative beyond rhetoric. During Virbhadra Singh’s 2012-17 chief ministership, more than 42 new government degree colleges were opened, raising the number of such institutes to 119 at the time. The face of primary education in Himachal Pradesh was also transformed in Singh’s tenures, under which most of the policies were framed, from the 1980s to the 2000s. Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze acknowledge this in their book Uncertain Glory: India and Its Contradictions (Princeton University Press, 2013).

“Some say we will bring the Delhi model, others say we will bring the Punjab model. But in Himachal only one model has worked and that is the Virbhadra Singh Vikas Model”, says Vikramaditya, promising to adapt and take his father’s legacy forward.

Vikramaditya Singh talking about the“Virbhadra Singh Vikas Model’

Activism over politics

The third weapon in Singh’s arsenal is his appeal to the youth, government employees, and farmers of the state. His rallies focus on addressing their concerns, particularly issues of unemployment and agriculture.

The Congress has recently promised employment to 500,000 youth of the state if it is voted to power. It has also assured farmers and horticulturists that they will play a part in deciding the price of their produce. Leaders like Vikramaditya Singh have played a major part in rolling out such poll promises.

Observers note that Vikramaditya’s on-ground approach supporting the issues of these communities is more like an activist than a politician. This may be why he is the most ‘followed’ opposition leader in Himachal Pradesh on various social media platforms, with over 287K followers on Facebook and close to 55K on Instagram. Many of his speeches broadcast on Facebook live sessions reach thousands.

This also makes him the most targeted opposition leader with the BJP and AAP gunning for him on social media. With no chink in the governance front to exploit, the criticism can only take up the issue of dynastic politics.

“The attacks have not diminished his popularity and he continues to receive massive public support for his rallies and outreach programmes from all sections of society.” says Madan, editor of Himachal Watcher, the state’s oldest online English magazine.

Vikramaditya Singh uses the shield of “Himachaliyat” and “Virbhadra Singh Vikas Model” to counter political rivals. Visual by artist Deepak Saroj in Noida

The way ahead

Observers believe that Vikramaditya Singh’s activism and his narratives of Himachaliyat and the Virbhadra Singh Vikas Model may help the Congress inch ahead of the BJP and AAP in Himachal Pradesh. Many traditional Congress voters who had moved away from the Congress in the last election may return to its fold.

“Vikramaditya Singh needs to be credited for the re-emergence of the INC in Himachal Pradesh as he is one of the few who understands that for insuring victory merely revolving around issues surrounding roti, kapda and makaan (food, cloth and shelter) is not enough and a strong counter-narrative is needed to take on the BJP & Co,” says, Amit Pal Singh, General Secretary, Himachal Pradesh Congress Committee.

Now the question is, will the Congress high command in Delhi look beyond its centrally managed election management machinery and boost this successful approach.

That, only time – and the upcoming polls – will tell.

Disclaimer – Opinions expressed in this article are strictly personal.

Opinion

Paradox in Hatti Community’s Demand for Tribal Status

By – Dr. Devender Sharma, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Government Degree College, Chail-Koti, Shimla District (Himachal Pradesh).

The opinion piece deals with the paradox over the demand for Scheduled Tribes (ST) status by the electorally-influential Hatti Community in Sirmaur District of Himachal Pradesh. Different socio-economic and political factors have made this issue complex and as political parties, especially BJP and Congress are doing their best to woe this community for electoral gains. Only time will tell what is in store for the community as a whole and the parties involved.

Hattis have had a long-standing demand for Schedule Tribe status since 1967 when such status was accorded to the people of the community living in Jaunsar Bawar (present-day Uttarakhand), a part of the wider Western Pahari Belt which sshares a similar culture, territorial contiguity and a common border with the Sirmaur district. The 0.35 million strong Hatti community consists of 14 clans and is spread across 154 Panchayats in the Trans-giri region. The community through its Central Hatti Committee succeeded in 2009, when their demand was included by the Bharatiya Janata Party in its manifesto. Hatti leaders have been mobilizing people by holding Khumblis and have continuously put pressure on the government to expedite the matter. Many within the state have supported their cause but the same has been opposed by Scheduled Caste communities and other backward classes making this issue a paradox.

Understanding The Community

The word ‘Hatti’ comes from ‘Haat’ which means a shop. The Hattis are a close-knit community who derive their name from their traditional occupation of selling home-grown crops, vegetables, meat, and wool at small-town markets known as ‘haats’. Back in the days when there were no roads or shops in Sirmaur, people used to carry agricultural produce to the markets in towns like Vikasnagar, Dehradun, Kalsi and Paonta Sahib. The produce would be traded for back salt, oil and spices. The shopkeepers in those towns used to call these people Haati.

The present population of the Hattis is estimated at around 3 lakhs. Hattis are divided into fourteen castes. However, a fairly rigid caste system operates in the community — the Bhat and Khash are considered upper castes, while several castes come under the scheduled castes and other backward classes. Inter-caste marriages within the community are traditionally discouraged. The Hattis are governed by a traditional council called ‘khumbli’ which, like the ‘khaps’ of Haryana, and Western Uttar Pradesh, decide community matters arbitrarily despite the establishment of the Panchayati raj system.

Traditional Elites and Role of Khumbli in Caste Divided Society

In rural Sirmauri society, the traditional elites still have a dominant position in social as well as political spheres. Most of the Lambardars, Zaildars and Pujaris are on the chair of formal establishments and control the informal as well as formal structures simultaneously. The objectivity of these Khumblis is questionable because the decision-making process is controlled by Rajput’s and Brahmin’s due to their ascribed caste supremacy. On the other hand, the Scheduled Castes are denied to play any role in the Khumbli. They are under a state of dominance as their whole socio-economic life is dominated by the village Devta. Any violation of rules framed around the Devta institution turns up the ‘Dev Dosh’ (divine wrath) upon them.

The Devta institution also decides the relations between different castes and assigns them work with some promises among different castes which is known as ‘Akhar Paur’. The functions of the Khumbli are undemocratic and against the egalitarian social order as the Scheduled Castes and women are excluded from the deity institution due to hierarchical social ranking and ritual impurity.

Power structure is dominated by upper castes on the basis of three attributes of dominance viz, ritual status, land holdings and numerical strength. They occupy land holdings which are mostly fertile, whereas the depressed castes have very less land and that too is usually unfertile. The traditional village elites the Lambardaar and the Zaildaar are mostly in possession of the land. Even with the introduction of new democratic institutions, caste panchayats are not losing their significance and caste sentiments continue to be exploited to obtain political power in formal PRI’s.

Present conflict has also had its roots in HP Village Common Land, Vesting and Utilization Act of 1974 by which the Shamlat land given after independence was taken back from the peasants. Under the Reorganization Act 1948, Land Ceiling Act 1972, HP vide Land Estate Evacuation Act 1954, the government procured most of the land from the princely states and big landlords and further from the Shamlat Pool. It was distributed to poor peasants, landless and dalits. In the year 2001, the BJP government made an amendment in the 1974 Act and they were made the owner of that land. Then, in 2017 the government made a law which had provisions concerning taking back the land from new landholders and distributing it to old landholders. The same has triggered the conflict between dominant and dominated caste groups.

Fear of Scheduled Castes and Other Backward Classes

The region is witnessing growing opposition from the scheduled castes and backward communities to the government’s move of granting ST status to the Hatti community. They fear that they would be deprived of their constitutional rights if ST status is given. Recently, Bhim army chief Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, while addressing a rally in Shimla, said that a grant of ST status would give upper castes the license to further exploit the Dalits. Sirmaur has the highest population of SCs in Himachal Pradesh. According to the 2011 census, Sirmaur has a total population of 5,29, 855, out of which 1,60,745 or 30.34 percent belong to the SC category. In some blocks of Sirmaur like Rajgarh and Sangrah, the dalit population is as high as 45 percent and 40 percent respectively. Atrocities reported against Dalits are also highest in the Trans-giri region.

Besides this they also have the fear that after the declaration of ST status to the Hatti Community they would be losing SC and OBC reservations and they will become an underdog in competition with dominant castes. Dalit activists say that no doubt Sirmaur continues to be one of the poorest and backward areas of Himachal, but what it needs is special financial packages and good developmental plans, not ST status at the cost of SC communities. “To say that only ST status would bring in development here is wrong. So much is already happening in the Trans-giri region in terms of connectivity and facilities including those of health and education. What we require today is a final development push through special packages,” says Ashish Kumar.

Perspective of Hatti Leaders

On the other hand, Haati leaders say, it’s a genuine demand and would benefit all castes and the entire Trans-giri region. “These fears of the SC communities are meaningless and we are doing our best to dispel them,” says Amichand Kamal, the President of the Kendriya Haati Samiti (KHS). “To begin with, SC communities would have an option whether they want to avail reservation benefit as SC or ST like it happens in other scheduled areas,” says Kamal.

The Hatti leaders feel that their development has been stalled due to the absence of tribal status. “If we get the status of a tribe, it will give impetus to the development works in the area, as well as open employment opportunities for the people of our community,” says Amichand Kamal. Further, Ramesh Singta Chief spokesperson of the Shimla unit of the Central Hatti Committee says, “We have been peacefully raising this demand for a long time. But now, the Hatti community has decided that if there is no right to tribal status, then we will not be exercising our right to vote,”

Political Gimmick

Due to BJP’s 2009 Lok Sabha election manifesto promise to give ST status to the Hattis, many members of the community sided with them. In 2014 Rajnath Singh also assured the same to the community in a rally in Nahan, Sirmaur. Then in 2016, the then Congress Chief Minister Virbhadra Singh moved a file to the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs asking for tribal status to the Trans-giri region, and Dodra Kwar in Rohru on the basis of a study conducted by the Tribal Affairs Institute, Shimla. The Union Ministry, however, said that the ethnography report about the Hatti community was inadequate, and sought a full-fledged ethnographic study. In March 2022, the Jai Ram Thakur government sent a detailed ethnographic proposal to the Centre, seeking the inclusion of the Hattis in the ST list of Himachal Pradesh. But nothing has happened since.

The Way Forward

The demand for ST status for the Hattis has its socio-economic and political nuances making it more complex. Supporters of the demand extend two arguments; one of the Lokur Commission criteria for the establishment of ST status, where they try to establish their geographical and cultural contiguity with the Jaunsar and Bawar region of Uttarakhand which has been given tribal status. But the claim raises conceptual doubts, as the primitive traits among Hattis were not communal as the name of the community itself suggests its character as a surplus-producing community having class stratification.

Secondly, their socio-economic backwardness and their belief that giving tribal status may possibly speed up the development process in the region. Again, this argument also seems puny as almost sixty years of changes have transformed these societies from backward tribal societies to more developed societies with more modern markets and social-political structures. The change must be recognized.

Thus, the issue of the ST status seems more of a political issue in terms of the BJP wanting to strengthen its grip in the area which has largely been a congress bastion.

On the flip side, the present conflict and more specifically the opposition by the scheduled castes and other backward castes of this demand must be seen in terms of the present power structures in the region.

Coming to the bottom line, the solution to the present conflict seems to be based on the idea of an egalitarian and just society which would create a broader unity among the different sections of the Hatti Community. For creating this unity, it is essential to address the issues and the fears of scheduled castes and other backward classes which constitutes around 30 to 34 percent of the region’s population. Thus, alternative schemes of development must be explored for addressing the problem of backwardness and underdevelopment in the region.

Featured

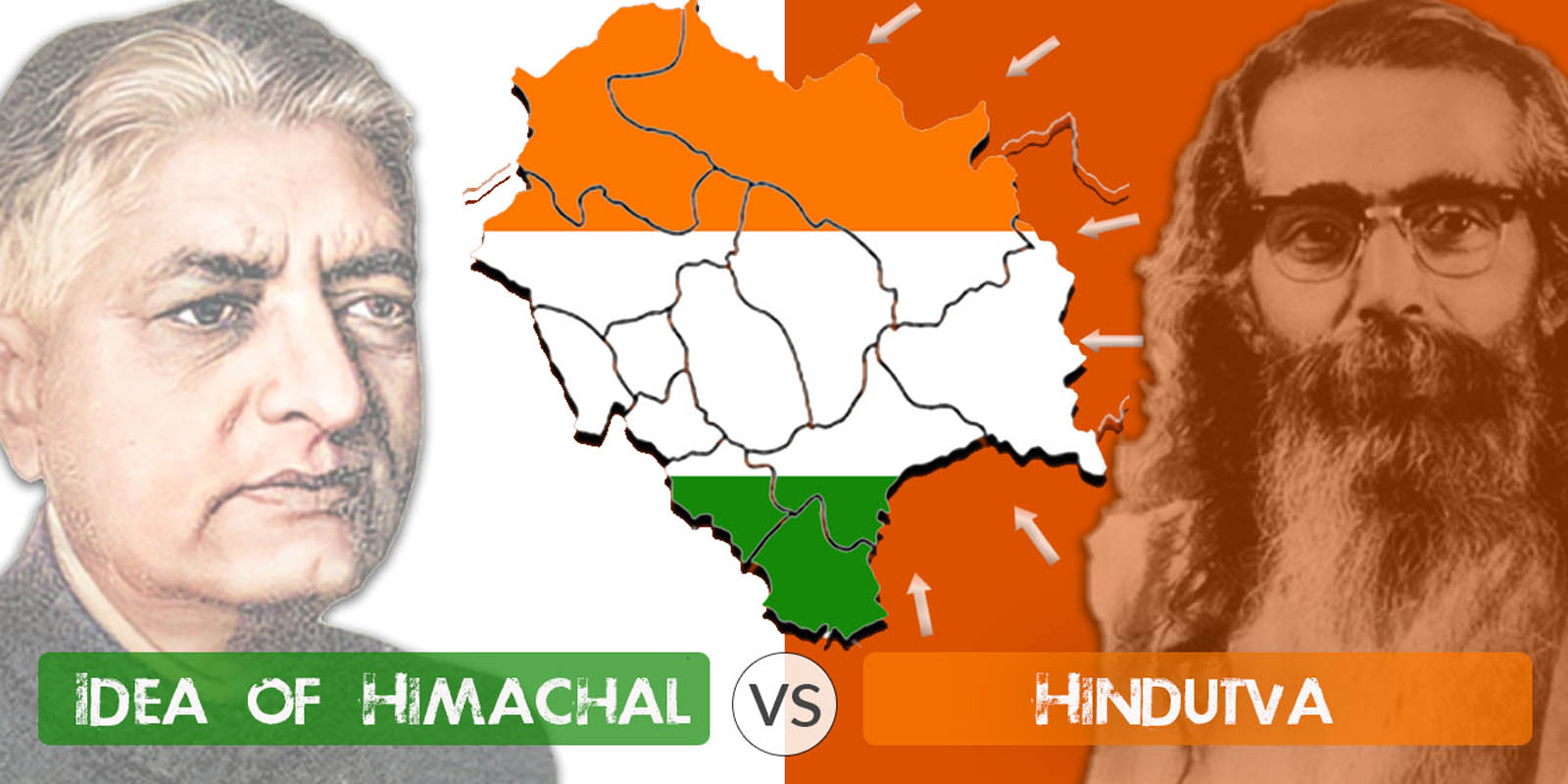

Himachali Sub-Nationalism: A Counter-Narrative To Tackle Hindutva In Himachal Pradesh

By – Vishal Sharma, a political science and public policy researcher/consultant. He holds an LL.M. in Legal & Political Aspects of International Affairs from Cardiff University (United Kingdom).

Himachali sub-nationalism can help tackle the Hindutva narrative in Himachal Pradesh which has long aimed at mainland-centric hyper-nationalism, cultural imperialism, linguistic imposition, and demographic change in the peaceful Western Himalayan province. A regional nationalism based counter-narrative that can be centered around the protection of Section 118 of the Land and Tenancy Act, 1972 and the revival of the Pahari (Himachali) language dialect chain is probably the need of the hour to keep away Hindutva and its caste/community and religion-based hegemonic politics from the province.

Himachal Pradesh and Hindutva

Himachal Pradesh has been a peaceful, riot-free, and harmonious province for the last 50 years. But as they say, nothing is perfect, similarly, a lot needs to still be achieved by the state on the policy front in relation to becoming economically self-sufficient and tackling the drug menace. On the other hand, in the political scheme of things the state till 2017 was governed on largely centrist lines that were slightly tilted towards regionalism. But post-2017 after Prem Kumar Dhumal’s shocking defeat things changed and Himachal Pradesh got its first purely Hindutva-minded Chief Minister. Jai Ram Thakur was handpicked by the RSS to lead Himachal Pradesh and take forward the Hindutva narrative which was largely on the backburner in previous BJP governments of the state as Prem Kumar Dhumal, a former Chief Minister of Himachal Pradesh was not from an RSS background and took a regional approach during his tenure, while Shanta Kumar another former BJP Chief Minister who although was from the RSS, but believed that Hindutva will not work in Himachal Pradesh.

Now coming to Hindutva, this idea as envisioned by MS Golwalkar is based on moral universalism and aims to establish a “Hindu Rashtra” (which has nothing to do with Hindusim and in a way misuses the religion) on the notions of civilizational colonialism. This very idea is used by the RSS in the present times to down ride the legal universalism-based constitutional idea of India. Over the last few decades in the public sphere, the idea of Hindutva has overshadowed the idea of India in especially the Hindi heartland, and in the coming decades, the RSS is looking to expand this mainland centric civilizational notion to the culturally different and non-mainland areas of especially the South of India, the North-East and the Far-North (Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, and Himachal Pradesh). Himachal Pradesh is high on their radar as they have their own government at place, and it can be said that over the years their narrative has gained some ground in ideally peace-loving Himachalis who were always seen to be non-supporters of such rigid ideologies whether it be on any side of the political spectrum. But the reverse seems to happen, and social engineering tactics have led to many moving towards Hindutva. On the flip side, those favoring the idea of India and other similar narratives have become silent due to the weakening of institutional setups which gave space to them.

The idea of Himachal and the grant of statehood

Moving on, Himachal Pradesh as I understand became a full-fledged constitutional state due to the efforts of our forefathers who envisioned a multicultural hilly province where people from numerous cultural zones like the Upper Western Pahari zone (includes parts of Shimla, Sirmaur, and Solan districts), Central Western Pahari zone (includes parts of Kullu, Mandi, and Bilaspur districts), Lower Western Pahari zone (includes parts of Hamirpur, Una, Kangra, and Chamba districts), Punjabi zone (includes parts of Una and Solan districts) and the Trans-Himalayan zone (includes parts of Kinnaur and Lahaul and Spiti) could live together, no matter what their ethnicity, religion or caste/community. This in fact can be termed as the idea behind the creation of Himachal, and to bring this idea into fruition in the 1950s and 60s the founding fathers of Himachal Pradesh led by Dr. YS Parmar worked beyond party lines to attain statehood for this hilly region stacked between Punjab (then Greater Punjab) and Himachal (then a UT). Geographical and linguistic parameters were set for the attainment of statehood and its unity, which can be considered as a very welfare-oriented and progressive approach, especially in a country where most of the political narratives are set on caste/community and religious lines.

The statehood movement was not merely an Indian National Congress (INC) exclusive movement and leaders from across the political spectrum did their bit. Some names which deserve special mention apart from YS Parmar were INC’s Tapindra Singh, Padam Dev, Vidya Dhar, Brahma Nand, Guman Singh and Amin Chand, revolutionary leftist leaders like Comrade Ram Chandra (INC) and Paras Ram (CPI), veteran Jan Sangh (now BJP) leaders like Daulat Ram Chauhan and Kishori Lal, and lastly regional stalwarts like Thakur Sen Negi and JBL Khachi. Through a study of the debates of that time, one also comes to know that all of them stood up in their own way and form for the Himachali cause putting aside their party ideologies. The INC and Jan Sangh (now BJP) leaders questioned the centrist attitude of their parties while leaders like Comrade Ram Chandra crossed all limits going to the extent of even warning the government of India in one of his addresses that a revolution may take place if statehood was not granted. Thakur Sen Negi and JBL Khachi were also so much into the Himachali cause that to strengthen the Himachali regional identity they formed the Lok Raj Party which was the first regional party of Himachal Pradesh. Thus, due to their effort statehood was finally attained in 1970-71.

The next steps in strengthening the idea of Himachal were also laid through the passage of Section 118 of the Land and Tenancy Act, 1972 which limited anyone from outside the state to buy agricultural land here, a boon for the Himachali people (who were mostly farmers) at that time, even till now this section is of utmost importance to Himachalis as it has helped in the protection of the distinct cultural identity of the state and has stopped demographic change. Another step in this direction was the unanimous passage of a resolution in the HP assembly in 1970 which declared Pahari as the mother language of the state, though over the years not much was done for the development of the language dialect chain but still people take pride in having this distinct linguistic identity. Dr. YS Parmar, Himachal’s first Chief Minister played a crucial role in both these initiations and paved the way for what according to me are the two pillars upon which Himachali sub-nationalism can be based, i.e., Section 118 and the Pahari (Himachali) language.

Need for Himachali sub-nationalism and its conceptualization

As stated earlier, in the initial years of statehood a lot was done to strengthen the idea of Himachal but slowly and steadily things started to change post-1975 and as the Delhi Darbar started becoming stronger, Shimla kept losing hardcore regionalists. Though still with the welfarist and progressive constitutional setup at bay things were going well with a hint of regionalism being used time in and time out by the principal parties in power. But as the Hindutva bandwagon reached Himachal Pradesh in 2017, things changed, and the moral universalism of Hindutva started questioning the constitution-based legal universalism. The public institutions started getting hijacked and the saffronisation of the public sphere started taking place. From RSS backed MLA’s being given Cabinet berths to other RSS ideologues getting appointed in important political positions, from grooming the next generation of BJP Himachali leaders in the RSS Shakhas to efforts towards the dilution of Section 118 of the Land and Tenancy Act, 1972, from imposing Sanskrit as the second official language of the state and sidelining the Pahari language to spreading communal tensions by doing D2D campaigns in favor of CAA and NRC, from spreading Islamophobia by terming Tablighi Jamaat followers as human bombs during the early days of the COVID-19 crisis to actively considering setting up Swarna Aayog (a commission for upper castes). A lot was done over the years which goes against the basic nature of this peaceful province and its polity.

This is in fact just the beginning, as recently the RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat launched a three-year roadmap in Himachal directing its office bearers to take Shakhas to the level of gram sabhas in Himachal Pradesh before 2025 (their centenary year). One can only imagine that if so much has been done in a short span of time what will happen if the BJP comes back to power. Many although are skeptical whether the BJP will come back to power as since the last three decades every five years there is a change of regime in Himachal but the recent assembly election results in Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand show a different story altogether and nothing can be taken for granted. RSS’s Hindutva narrative is so dear to them that they can cross any limit to bring BJP into power in Himachal Pradesh and a mere tackling them on public policy issues revolving around Roti, Kapada, and Makaan will not help.

Thus, this is where the Himachali sub-nationalism narrative comes into play which the principal opposition parties should look to use. In fact, such is the trend in the last few years that in non-mainland states only regional nationalism has served as a counter to Hindutva nationalism. Sub-national counter-narratives worked well in non-mainland states like West Bengal and Tamil Nadu where local Bengali and Tamil identity narratives were used to constantly keep away the alien Hindutva identity. Invariably, in the long run, this counter-narrative seems to be the only way through which the federal structure of the country can be protected from Hindutva, as well as the survival of the constitutional layers of this country can be ensured. A positive response towards such a counter-narrative in Himachal could lead to a wider wave in especially the entire Far-North.

Upcoming assembly elections a referendum on Hindutva

The upcoming assembly elections in Himachal Pradesh will definitely be a referendum on Hindutva. With the people of the state having to choose between the narrative of Hindutva or any counter-narrative of the opposition. But the opposition should keep in mind that in order to defeat morality-based narratives a counter morality-based narrative is required and thus Himachali sub-nationalism centered around the protection of Section 118 and the revival of Pahari (Himachali) language dialect chain can be a counter-narrative which the people of Himachal Pradesh may be looking for. They could be asked to simply decide whether they prefer being a “Himachali” or a Hindutva subject divided into castes/communities like Brahmins, Thakurs, Punjabi Refugees, Khatris, Soods, Mahajans, Gaddis, Gujjars, SCs, STs, etc, or into religious identities like Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Muslims, Christians.

In the end, all one can say is that we may sadly see the demise of the idea of Himachal if Hindutva is not defeated this time, and if this civilizational narrative is victorious then the traditional political spectrum in Himachal Pradesh will perish and the Hindutva political spectrum will rise. This may further lead to the emergence of new narratives which would be invariably aligned with the idea of Hindutva and not with the idea of India.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Himachal Watcher or its members.

Home Decor Ideas 2020

Home Decor Ideas 2020